Museum of Northern History, Kirkland Lake

White Water Gallery, Northbay

Temiskaming Art Gallery, Haileybury

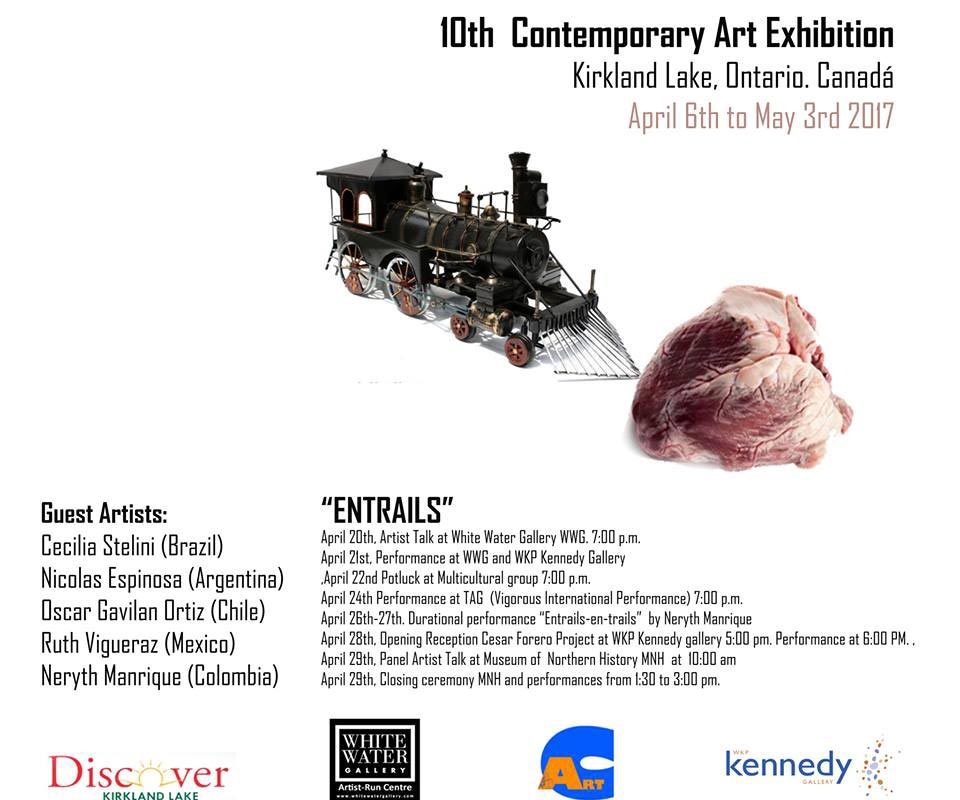

Entrails: Collective Catharsis, Fragments of Dignity

(April 20-April 29, 2017 at the White Water Gallery and WKP Kennedy Gallery, North Bay; Temiskaming Art Gallery, Haileybury; The Museum of Northern History, Kirkland Lake in Ontario, Canada)

Entrails, as the organizational theme, supposes excavation as an act that is necessary to bring the material and topic into focus. Whether physical or metaphysical, the exposure of entrails requires effort, if not force. Entrails connects the performances of Ruth Vigueras Bravo (México), César Forero (b. Colombia/ l. Canada), Oscar Gavilán Ortiz (Chile), Neryth Yamile Manrique (Colombia), Nicolas Spinosa (b. Argentina/ l. Uruguay/Spain), and Cecilia Stelini (Brazil). Through choreographed sequences in spaces that geographically span the area between Toronto and Kirkland Lake, the performances of Entrails embody aspects of social and cultural violence, personal pain, desire, and love. A series of performances around the theme of Entrails could shock and traumatize, but, here, collectively, the actions embody the dignity in catharsis and, perhaps, the restoration of dignity through catharsis and collective attention.

Each performer’s body and the hearts, intestines, and blood used in the actions give flesh to experiences of marginalization and internalization, including physical, emotional and economic suffering. The series begins with Manrique’s bridging of two galleries (WKP Kennedy Gallery and White Water Gallery in North Bay) through her movement from one to another. Her simple physical transition between internal and external (public art space and public street, one interior space to another) signals a practice in which her body consciously responds to the built environment, which in turn stands in for abstract societal constructions and the palimpsest of memories that overlay site.

This introduction serves as shorthand for the shifting between psychological and physical spaces, the distance between the corporeal and abstract that will again and again resurface in the performances. The chicken hearts used in her first performance, Manrique states, are toy-like. Indeed, painted in gold powder, they become cute treasures that are gifted to audience members along with praise: you have a golden heart. The play of words and action naturally construct a bridge between the golden heart on view that has been clearly dubbed symbolic, and the person’s actual organ as something that not only is essential for life, but that also carries metaphorical weight. To add to the multifaceted readings of the heart, Manrique swallows a chicken heart submerged in wine. The gentle sweetness of painting small objects in gold and gifting them is countered by her consumption of the organ–an act that reminds the audience of the normalcy, sometimes callousness, of carnage. In her performances, the sweet is checked by something darker and more forceful, making the acts, in part, read as catharsis for violence endured.

Purification and healing are integral to the performances of Vigueras and Stelini. Each addresses

personal physical illness and uses biographical experience as metaphor and impetus for performing and healing. Vigueras’s own suffering of fibroid disease is the impetus for much of her work presented in Entrails. For her, the body is symbolic and anthropological, and Confesiones bajo la lluvia roja, installed in the Museum of Northern History, is based on a project with a group of women who also suffer from hormonal or psychosomatic disorders. Her engagement with the group results in visual (the selection and modification of a flower to externalize self and experience) and a written testimonial. Vigueras uses blood (or a symbolic substitute like red string) as purification, making the connection to menstruation. Menstruation is purification, but it is also frequently the source of discomfort, annoyance or pain. There’s labor required to release and heal, as alluded to in Vigueras’s work, and power in collective validation.

The violence of healing is tantamount to Stelini’s performance work that here features a compilation of video clips of her own open-heart surgery as backdrop to her labor of stitching and/or cutting of organs. Stelini recreates a surgical experience as she joins heart and fish, inviting speculation on the sacred and profane symbolism attached to each. Her performances allude to an interplay of masculine and feminine, the reciprocity of giving and receiving, the violence of patriarchal dominance, and the idea of love and its absence. The invasiveness of surgery and the vulnerability of the patient are made plain. Yet against external forces, the body and mind are shown resilient. The versatile act of sewing unites the exposed physical terrain of Stelini’s body with a complex emotional landscape that forms in response to social and cultural binaries.

While Stelini commands the trained force of a surgeon in her actions, Forero harnesses the grace of a dancer to move through age-old dualities. Figures tumble through Forero’s paintings, which are enlivened by the words, movements and aesthetic of a costumed dancer and singer. The radiance of colors and the play of bodies signal an alchemical process that forges transformation. Unlike the other performances, the tone is pleasurably fantastical. The objects and performance narrate the shape-shifting quality of internal desire.

Desire manifests in Spinosa’s performance at the White Water Gallery too, but here, it circles back to the theme of consumption and is externalized. Exposure in Spinosa’s performances is made an ironic game that both replicates and criticizes the market as a global capitalist system. Spinosa exposes his own body as subject (a performer of cultural labor) and consumable object. Through this act, “contemporary art” is implicated with the other intersecting markets that traffic services and goods. Humor and irony coalesce as a veneer that protects the vulnerability of being exposed and serving oneself up as “the cheapest meat on the market.” Performance overtly displays the labor of the artist, complicating the conception of body as subject and object.

Gavilán extends Spinosa’s exploration of “contemporary art” as a system that privileges the production of object over subject to the mining industry in Lota–a scenario that is both more specific in its local ties and similarly general in its allusions to the abuse of social and economic systems. The failing of neoliberalism is eloquently expressed not only in performance, but also in the book Esto es normal: Epílogo de un patrimonio olvidado. In each, the prosthetic limb symbolizes a violent loss, as well as the violence of a system that systematically cuts its losses. But the caress and loving manipulation of the prosthetic, asserts desire, and inherent in this a longing. The longing though is bound to an illusion of progress. The intestines and coal, as materials, are extracted innards from a body and the earth respectively. They are products that set the stage for the progress of giving dignity to the displaced and wounded, and recognition that these conditions are not abnormal, but average.

The labor of finding, hauling, and giving new poetic life to physical or spiritual remains, became not just an individual, but also a collective effort in the preparation of each event. The collective force of the performances was reiterated and amplified through interactions with an audience who cautiously sought connection–a desire for association, or a desire to be pulled from routine or isolation. Entrails affirms a craving for human connection, validation and respect as one struggles to articulate the material and spiritual self against experience. It upholds that catharsis is liberation.